Palestinian Responses to the Beijing Declaration

This issue of Circumspection examines how Palestinian officials and observers have discussed the reconciliation agreement recently signed in Beijing by Fatah, Hamas, and 12 other Palestinian factions

By Raphael Angieri

(This article was first published in collaboration with the ChinaMed Project, a research initiative of T.wai, the Torino World Affairs Association.)

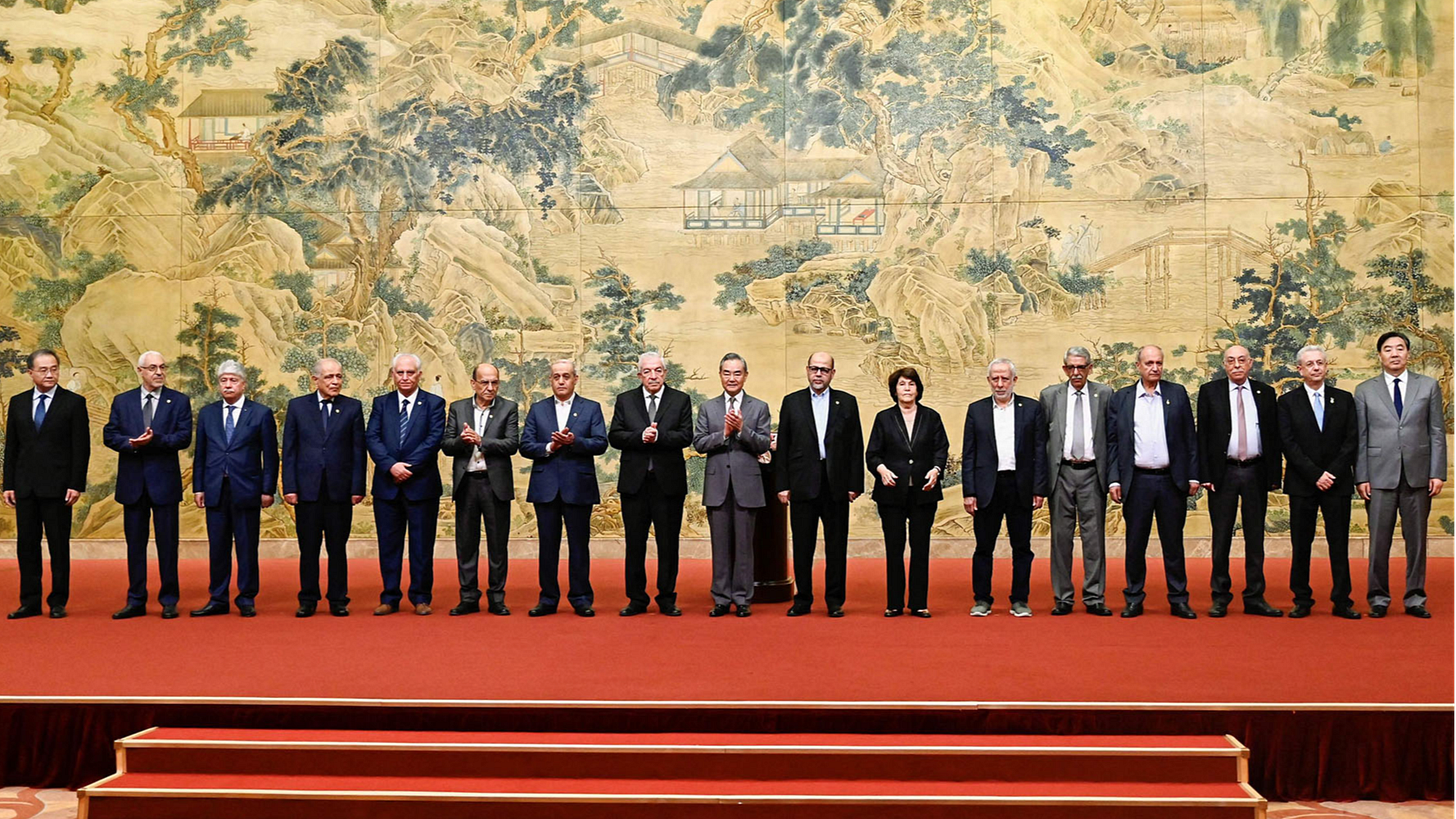

On July 23, 2024, in a development feted by Chinese state-run media as a triumph of the country’s Middle East diplomacy, representatives of 14 Palestinian factions, including Fatah and Hamas, jointly signed the “Beijing Declaration to End Division and Enhance Palestinian National Unity” at an event presided over by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.[1]

Issued following three days of talks in the Chinese capital, this “Beijing Declaration” is the first formal agreement to have been reached by the factions since the onset of the Israel-Gaza war in October 2023. Previous high-level meetings in February and April, held respectively in Moscow and Beijing, concluded without achieving visible results.

According to versions of the declaration circulating online, including photographs of a signed text published by Palestinian news outlet Watan, the factions agreed, among other things, to the formation of an interim national unity government operating under an inclusive leadership framework. This government would exercise authority over all Palestinian territories, with a mandate to unify institutions, begin reconstruction of Gaza, and prepare for general elections. [2]

The declaration joins a long list of accords aimed at Palestinian reconciliation since disputes surrounding elections in 2005-2006 resulted in a breakdown of cooperation between the major factions.[3] The pre-October 7 status quo, where Hamas ruled unilaterally inside the Gaza Strip, the borders of which remained under Israeli control, and Fatah dominated Palestinian governance in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, has been disrupted by the current war in Gaza, leading to a renewal of efforts ostensibly intended to enhance coordination.

Hailed by many in China as an important step toward resolving the ongoing Middle East crisis, the Beijing Declaration has in Israel largely been ignored, downplayed, or panned for legitimizing Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), which are classified as terrorist organizations in the United States and other Western countries.[4]

Against that background, this issue of Circumspection focuses on Palestinian narratives regarding the Beijing Declaration.

Signatories’ follow-up to the agreement has been equivocal. Publicly, Fatah leadership expresses support for unity, yet behind closed doors, top officials have cast doubt on the seriousness of any deal which could undermine Fatah’s influence, even as voices of opposition within the West Bank political establishment call for institutional reform and concerted action. Hamas, for its part, asserts its readiness to play a subordinate role in a unity government, but has prevaricated on the specific ideological concessions it is willing to make as a part of such an arrangement.

Palestinian observers have underscored the potential significance of concessions made by Fatah and Hamas, while also acknowledging unresolved areas of disunity and questioning the credibility of both factions given their past failures to follow through on commitments. Examining the structural forces which fashion the contours of the reconciliation file and may thus influence its outcome, analysts moreover see the leadership in Ramallah—as the party most likely, but not certain, to inherit the governance of Gaza on the “day after” the war—to be leveraging the agreement as a means of placating pro-reform forces internally, gain validation from key players in China and Russia, and set up a contingency ‘unity option’ to be activated in case efforts are made to exclude it from a post-war role in Gaza.

Fragmented Response from West Bank Leadership

Fatah’s public messaging on the Beijing Declaration has been muted. But in anonymous interviews with the press, members of the party’s senior leadership have seemingly conducted a campaign to backtrack on commitments, depicting the agreement primarily as a diplomatic move to build on relations with China. Dissident voices, meanwhile, have pushed for implementation.

In a rare public comment, the Fatah Central Committee, responding to an August 7 briefing on the declaration—two weeks after its signing—“emphasized the urgent necessity of restoring national unity among Palestinian factions as quickly as possible,” without specifically endorsing a unity government, inclusive leadership, or any of the other elements to which the party had formally agreed.[5]

In more confidential settings, a different narrative has been offered to the press. An affiliate of Fatah’s government who participated in the signing of the Beijing Declaration, but requested anonymity to speak on the record, told The New Arab:

“We made important concessions to maintain our relationship with China, such as agreeing to the national unity government and unified leadership framework, among other things. These are major developments, but nothing will happen on the ground.”[6]

Likewise, journalist Jack Khoury, writing for Israeli newspaper Haaretz, reports being told by an unnamed senior Fatah official that the decision to establish a national government depends on external factors, such as the United States, Israel, and the Arab countries, but that the events of recent months require the party to present the appearance of advancing Palestinian unity.[7]

In contrast, at least one disaffected member of Fatah leadership, as well as non-Fatah figures associated with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the multi-party coalition dominated by Fatah, have endorsed the establishment of a unity government and stressed the need to follow up with concrete measures.

Deviating from party boilerplate, Mohammad Shtayyeh, a senior Fatah official and Prime Minister of the West Bank’s Palestinian Authority (PA) until his resignation from that position in March 2024, reportedly called the statement “serious,” but insisted that “The general public wants results, they don’t want papers. They want practical steps in the right direction.”[8]

Similarly, Mustafa Barghouti, Secretary-General of the Palestinian National Initiative and himself a signatory to the agreement, asserted that the Beijing Declaration “represents an important, advanced, and serious step towards achieving Palestinian national unity in the face of the crimes of genocide, annexation, and settlement,” emphasizing:

“The key now is to begin the immediate and actual implementation of what was stated […] and to leverage the momentum of support from brotherly and friendly countries with significant influence, such as China and the Russian Federation.”[9]

In media interviews condemning the assassination in Tehran, allegedly by Israel, of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh on July 31, Ali Faisal, Deputy Chairman of the Palestinian National Council and Deputy Secretary-General of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, also a signatory party, took an even stronger stance on behalf of concertation with Hamas, calling for “a meeting of the unified leadership framework to carry out the Beijing Declaration and form a national unity government under the reference of the PLO” to meet this collective challenge.[10]

Backing from Hamas, but Obfuscation on Terms

Directly involved in the ongoing war and humanitarian crisis in Gaza, where over 40,000 people have reportedly been killed and nearly two million displaced as a result of Israeli assaults, Hamas leadership has responded to the Beijing Declaration by endorsing its central proposal of forming a unity government. This position would seem to correspond to the group’s previously expressed interest in developing a non-partisan administrative apparatus for Gaza—even at the cost of ceding direct political control—to ensure Palestinian governance on the “day after” the war.[11]

Husam Badran, head of Hamas’s national relations office and a member of its political bureau, described the agreement as a “positive step” toward the goal of “forming a Palestinian national unity government to manage the affairs of our people in Gaza and the West Bank, oversee reconstruction, and prepare conditions for elections.”[12] Badran further affirmed:

“The national solution represents the best and most suitable response to the Palestinian situation after the war, serving as a barricade against all regional and international interventions that seek to impose realities contrary to the interests of our people in managing Palestinian affairs.”

In his focus on the most concrete elements of the Beijing Declaration, e.g., forming a body to administer basic services to Palestinians in crisis, and his prioritization of territories already under at least partial Palestinian governance prior to the war—Gaza and the West Bank as opposed to East Jerusalem or Israel’s pre-1967 holdings—Badran appears to be treating the agreement as an expression of real and potentially achievable aims ostensibly shared across factions.

Nevertheless, Badran suggested a reluctance to fully endorse all parts of the declaration. He claimed that the text to which Hamas had agreed was “clear in its content, and not what has been published and circulated since yesterday,” although he failed to specify which elements of the publicly available texts might be problematic in Hamas’s view.[13]

The official statement from Palestine Islamic Jihad (PIJ), an offshoot of Hamas known to take positions representing the most extreme views of the larger Palestinian Islamic resistance movement, was more forceful and specific in its rejection of the published text of the Beijing Declaration. According to news reports, PIJ claimed the version of the text circulating on the web to be “inaccurate and mendacious,” asserting PIJ’s rejection of “any agreement which, by including international resolutions, might lead to recognition of the usurping Zionist regime, which has developed plans to destroy the Palestinian cause.”[14] PIJ would seem here to be commenting on a clause in the agreement committing signatories to establishing an independent Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital, “according to relevant United Nations resolutions.” These UN resolutions are controversial within the resistance movement comprising Hamas and PIJ for their recognition, explicitly or implicitly, of Israeli statehood on some portion of historic Palestine.[15]

Thus, while Hamas seems focused on practicable aspects of the agreement, the broad strokes of which are consistent with aims it has expressed elsewhere, rhetorical evasiveness from the movement itself, as well as outright denunciation from its splinter group PIJ, imply that internal disagreement is ongoing as to the ideological concessions considered acceptable in pursuit of achieving unity and preserving a level of Palestinian self-governance in Gaza.

Observers Note Convergences, Emphasize Prevailing Disunity

The terms agreed upon by signatories of the Beijing Declaration have ignited vigorous debate among observers, with opinions varying as to whether this accord represents a true convergence of factional positions, and may thus signal readiness to establish a unity government. The declaration’s reference to UN resolutions on Palestine, in particular, has attracted attention, with Chinese analyst Ma Xiaolin going so far as to claim that this clause signals “Hamas and PIJ accept Israel as a state and they don’t intend to recover all of Palestine but East Jerusalem, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.”[16]

Palestinian observers have adopted a more conservative stance. While they recognize the new precedent set by language used in the document, they also highlight areas where the factions are still far from aligned.

Ramallah-based analyst of Palestinian affairs Jehad Harb, in a letter to Watan, underscores that a number of key elements are introduced in the Beijing Declaration, such as “(1) the agreement in principle on the form of an interim Palestinian government, a ‘national unity government’; (2) the activation and regularization of an interim leadership framework; and (3) the tendency or threat to lean towards the East in Palestinian politics.”[17] In Harb’s view, the truly novel aspect of the declaration, though, is “Hamas’s commitment to the establishment of a Palestinian state according to UN resolutions.” According to Harb, this is the first time a commitment to the resolutions on Palestine has been issued “with such clarity, without caveats or explanations that could allow for re-interpretations of this text by Hamas leaders.” Hence, for Harb:

“This text represents a serious and fundamental shift in Hamas’s political thought, albeit a late one, which can be built upon in Palestinian politics to counter Israeli propaganda on the one hand and to achieve agreement on a unified political program for Palestinians on the other.”

Omar Al-Ghoul, a political observer who served as national affairs advisor under former PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, likewise acknowledges “positives” of the Beijing Declaration, and especially “the inclusion of Hamas and [PIJ] in the PLO, as well as recognition of [the PLO] as sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.”[18] However, for Al-Ghoul, ambiguities and inconsistencies within the declaration suggest unwillingness on the part of Hamas and PIJ to make the concessions necessary for unity.

Notably, the signatories’ commitment to UN resolutions is, for Al-Ghoul, noteworthy, but undercut by the “absence of a point regarding acceptance […] of international legitimacy resolutions to which the PLO, as sole legitimate representative, adheres”—in other words, the absence of a clause aligning all signatories with the PLO’s position recognizing Israel.[19] Al-Ghoul considers alignment on this point a condition for inclusion within the PLO, making its absence from the agreement a serious deficiency. Al-Ghoul further questions the insistence on an interim leadership framework and the failure to allot a role to the PLO “in managing the ongoing negotiations for a prisoner exchange deal and the cessation of the genocidal war.”

If Hamas were serious about unity, Al-Ghoul opines, it would subordinate itself to the PLO leadership and immediately involve that leadership in ceasefire negotiations, with no need for interim arrangements.

Finally, Al-Ghoul points to vagueness on “mechanisms and parties responsible for implementation” as debilitating to the achievement of what he otherwise views as laudable aims, at least in principle.

In a column for Al-Quds, Hamadeh Faraneh, a current member of the Palestinian National Council and former member of both the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the Jordanian House of Representatives, takes an even dimmer view of prospects for unity, focusing on the unresolved and “prevailing state of monopolization, where Fatah monopolizes both the authority in Ramallah and the leadership of the PLO, and Hamas monopolizes Gaza alone since its military takeover and unilateral control in June 2007.”[20] Thus, according to Faraneh:

Unless both sides can overcome “the disease of unilateralism and exclusion,” and Hamas commits to “UN Resolution 181, which is the reference for the two-state solution, and Resolution 194, which indicates the right of refugees to return and recover their properties,” then little can be expected of the reconciliation process.

While much of the debate around changes in factional positioning has been centered on concessions to which Hamas and PIJ may or may not have agreed, analysts have also noted a re-alignment on the part of Fatah. Correspondent Naila Khalil writes for The New Arab that Fatah’s acknowledgement of resistance to occupation as a right guaranteed under international law, in particular, “represented a remarkable shift in the position of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and the Fatah movement” given the renunciation by Fatah and the PLO of violent resistance to occupation, under the Oslo Accords and subsequent negotiations with Israel.[21]

As with Hamas’s concessions, however, there is no certainty among analysts that this language constitutes a real break with Fatah’s long-held position, rather than a rhetorical move aimed, in this case, at boosting the party’s credibility among Palestinians frustrated by endemic disunity and the seeming passivity of West Bank leadership despite an ever-rising death toll in Gaza.

Structural Forces to Determine Outcome?

Looking beyond the text of the Beijing Declaration, Palestinian observers have also been attentive to the structural forces which set the stage for—and may determine the outcome of—the reconciliation process.

Hamas is seen by analysts to be playing for unity from a position of weakness, so as to avert its total exclusion from the political process following the war. Fatah, meanwhile, is thought to be responding to demands for reform and real solidarity with Gaza—demands arising from forces internal to Fatah and the PLO—even as party leaders hold out for the possibility that international powerbrokers allow them to extend to a post-war Gaza their already dominant role in the politics of the West Bank.

Hani Al-Masri, General Director of the Palestinian Center for Policy Research and Strategic Studies, focuses an editorial for Al-Quds on these structural forces. Acknowledging a campaign waged against the Beijing Declaration by “individuals associated with Fatah, [including] some of the president’s advisors,” who consider the agreement to be “a loud voice for nothing at all,” Al-Masri asserts that the declaration is not in fact meant to achieve unity in the immediate, but “to signal to America and Israel, and those who align with them, that there is an alternative which can be pursued if matters deteriorate,” meaning “if [Israel] continues to reject the return of the [PA] to the Gaza Strip and undermine it in the West Bank, and if regional attempts to bypass the Palestinian option continue.” [22] In other words, the declaration is a means for Fatah to begin setting up a contingency plan in case it is denied leadership of post-war Gaza.

This view is bolstered, according to Al-Masri, by indications from Fatah spokespeople that they intend for “the formation of the interim national unity government [...] and activation of the interim leadership framework to occur after the war ends, not now.” It would also explain why no timeline was set for next steps. For Al-Masri, the decisive element determining whether implementation of the agreement will be pursued lies in the outcome of the US presidential election:

“If Trump wins, the Beijing Declaration will be activated, because confrontation will prevail, while if Harris wins, the fate of [this agreement] will be that of previous agreements, because fantasies regarding […] a so-called ‘two-state solution’ will continue to predominate.”

Al-Masri argues that this contingency stems from a situation wherein “Hamas needs unity and the cover of Palestinian legitimacy more than ever, to thwart plans to eliminate it, while the formal Palestinian leadership [Fatah] may need unity or may not,” and thus “treats unity tactically, merely as a card to be used in case of need, when the existence of an agreement with Hamas would offer significant advantages.” This use case would be activated, in Al-Masri’s view, only if Donald Trump is elected and seeks to bypass the Palestinians in post-war Gazan governance. Al-Masri considers a Harris administration as more likely to seek the PA as a partner in governing Gaza, leaving Fatah with the option to dominate the governance process unilaterally and sideline Hamas.

As for China’s role in the reconciliation process and support for Palestinian statehood, Al-Masri validates critiques noting the superficiality of Chinese contributions compared to other countries in the Global South, such as South Africa. After all, China has shown no willingness to “punish Israel, with whom it has special relations” by “imposing a solution within the UN Security Council, international institutions, and beyond […] or by exerting more influence and providing more aid.”

But for Al-Masri, the current paucity of Chinese efforts to aid the Palestinian cause results more from the immaturity of this policy direction than a lack of will to push for a change in the status quo. Given the background of China’s longtime alignment with Palestinian rights and early recognition of the State of Palestine, along with the growing number of Chinese “proposals and moves to resolve conflict in the region,” exemplified by its active role in the Riyadh-Tehran reconciliation, Al-Masri sees the Beijing Declaration to be just the beginning of the country’s push to “end US monopoly over the peace process.” Wang Yi’s call to “convene an international peace conference with broader participation, greater credibility, and more effectiveness” would be a case in point, in the estimation of Al-Masri, demonstrating the country’s willingness to invest further.

Naila Khalil, in her analysis of the “behind-the-scenes” action of the Beijing Declaration, likewise homes in on the power dynamics which may be determinative of what is to come. Providing context for the concessions made by Fatah so as to reach an agreement, Khalil reminds readers that “timing and crucial deadlines have been left under Abbas’s control,” such that:

“While some see a real change in Abbas’s position to align with the serious threats facing the Palestinian cause, other observers believe Abbas still to be ‘waiting and buying time’, merely advancing two steps within the same square.”[23]

According to Khalil, Abbas is attempting to balance several considerations, “the most important being a desire to maintain his relationship with China, which exerted considerable soft power to ensure the meeting’s success,” as well as the looming threat of a Trump presidency and pressures exerted by Arab countries. Externally, Abbas must meet the challenge of those in Israel and further afield seeking to “exclude the PA from the game” by using international forces such as the United Arab Emirates to reduce or eliminate the PA’s role in post-war Gaza.[24] At the same time, internally, Abbas faces contestation by elements within the PA and PLO, including members of the Central and National Councils, to enact “fundamental change and genuine reconciliation to get the PA ready for the ‘day after’ the war,” meaning “real reform of the PLO and its institutions and an end to division.”

These external and internal factors would explain Abbas’s willingness to engage with Hamas and PIJ, making concessions to facilitate a ‘unity option’. But, in the words of Naila Khalil, “the devil is in the deadlines, this time around, and not in details that the factions have exhausted themselves discussing over the past 17 years.” That is to say, without a schedule to follow through on the agreement, it may be entirely inconsequential that Fatah has conceded, for example, to Hamas’s insistence that the interim leadership framework be a “partner in political decision-making” rather than expressly subordinate to the PLO’s Executive Committee. If Abbas is able to take direct charge of Gaza following the war, then the leadership structure will be a moot point.

Conclusion

As the war in Gaza grinds on, at the time of writing, unabated, leaving much of the Gaza Strip in ruins and exposing a large civilian population to bombardment, displacement, disease, and famine, the issuance of the Beijing Declaration has generated renewed attention to the inter-Palestinian reconciliation file, both internationally and among regional stakeholders.

In the wake of the agreement’s publication on July 23, the major players in the reconciliation process, Fatah and Hamas, have continued to express public support for the goal of a unity government. Anonymous statements by Fatah officials, however, have called into question the seriousness of the party’s commitment to the declaration, depicting it as a diplomatic move aimed at currying favor with China, even as dissident voices within Fatah, the PLO, and the PA insist upon a need for real unity to meet the challenges currently facing Palestinians.

Hamas, for its part, has been vocal in endorsing specific provisions of the declaration, most importantly that of establishing a unity government to administer a Gaza in crisis. Yet the movement has been equivocal about the ideological concessions it is willing to make in pursuit of that goal, for example, recognizing UN resolutions on the nature of a future Palestinian state.

Palestinian observers have debated the extent and significance of areas of apparent convergence signaled in the text of the Beijing Declaration, noting that agreement by Hamas to respect UN resolutions on Palestine would represent a shift toward the PLO’s position, while recognition by Fatah of Palestinians’ right to resist Israeli occupation would constitute a re-alignment toward the position held by Hamas. But no consensus exists among analysts as to whether these concessions indicate actual changes in viewpoint or simply rhetorical tactics meant to offer the appearance of unity.

With regard to the structural forces at play in the issuance of the agreement, as well as the likelihood that this agreement could result in the brokering of a unity government, Palestinian observers point to critical dynamics both internal and external.

Hamas, ostracized by international powers such as the United States, and still bogged down in a war which has been disastrous for its constituents in Gaza, is thought to be looking for ways to remain a player—even if in a diminished or indirect capacity—in post-war governance, ideally without compromising on core commitments including armed resistance. Fatah is under pressure from the Palestinian street and within the PLO to transcend partisan disputes, demonstrate solidarity with those suffering in Gaza, and reform its governance structures so that it can increase its impact on the ground. At the same time, as Fatah seeks to maximize its influence in Gaza on the “day after,” it faces the uncertainty of a US presidential election which may tilt international favor toward or against its participation in post-war governance. Taking part in the reconciliation process is thus seen as a means for Fatah to gesture at unity while hedging its bets.

Within these dynamics, the China factor is at once critical and ambiguous. Both Fatah and Hamas are thought to take an active interest in ingratiating themselves with China, as its diplomatic and economic engagement with the Middle East, and the Palestinian issue in particular, continues to intensify and break new ground. Given the country’s role in Saudi-Iran normalization and the vocal support it has given to Palestinian interests amidst the war in Gaza, China is perceived to be a potentially consequential player going forward. That said, China’s own motivations for involving itself in the reconciliation file—not to mention the leverage it can bring to bear or the lengths it is willing to go in pursuit of a resolution—have not received significant coverage from Palestinian observers, beyond noting the country’s apparent desire to establish itself as an alternative to the United States in a high-profile diplomatic arena.

Raphael ANGIERI (李少轩) is an independent foreign policy analyst specializing in the political economy of China, Sino-Arab relations, and Palestinian politics. He holds a B.Sc. in International Affairs from Georgetown University and an M.Sc. in International Development from Sciences Po Paris. Raphael previously served as a Fulbright ETA Fellow in Baqa, a partitioned town on the Green Line, and has nearly a decade of field experience between China and the Middle East.

You can reach Raphael on LinkedIn or the Platform Formerly Known as Twitter.

[1] Zhou Jin, Jan Yumul, and Mike Gu, “Palestine groups agree unity,” China Daily, July 26, 2024, link.

[2] Watan, “waṭan tanšur naṣṣ ʾiʿlān bikīn’ .. al-faṣāʾil tattafiq fī al-ṣīn ʿala taškīl ‘ḥukūmat muṣālaḥa waṭaniyya muʾaqqata’ [Watan publishes the text of the ‘Beijing Declaration’ .. factions agree in China to form an ‘interim national reconciliation government’],” July 23, 2024, link.

[3] Institute for Palestine Studies, “Hamas-Fatah Reconciliation Attempts: 2005 - present,” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question, August 1, 2024, link.

[4] Amanda Xinyi Chen, “Israeli Media Reacts to the Beijing Declaration,” ChinaMed Project, August 7, 2024, link.

[5] Palestinian Liberation Organization, “al-lajna al-markaziyya liḥarakat ‘fatḥ’ tuʿqid ʾijtimāʿan fī rām allāh [The Central Committee of the ‘Fatah’ Movement holds a meeting in Ramallah],” August 7, 2024, link.

[6] Naila Khalil, “kawālīs ittifāq al-muṣālaḥa al-filasṭīnīyya fī bikīn… al-šayṭān fī al-mawāʿīd [Behind the scenes of the Palestinian reconciliation agreement in Beijing… the devil is in the deadlines],” Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, July 25, 2024, link.

[7] Jack Khoury, “ḥamās u-faṭaḥ siqəmū b-sīn ʿal “šiqūm ha-ʾaḥadūt,” ʾaḫ la-haṣhara ʾên kol mašmaʿūt maʿśīt [Hamas and Fatah agreed in China on ‘restoring unity’, but the statement has no practical meaning],” Haaretz, July 23, 2024, link.

[8] Adam Rasgon and Alexandra Stevenson, “Palestinian Factions Hail Declaration of Unity in Beijing, but Skepticism Is High,” The New York Times, July 23, 2024, link.

[9] Watan, “d. muṣṭafā al-barġūṯī: ʾiʿlān bikīn li-ʾinhāʾ al-inqisām ḫuṭwa hāmma mutaqaddima wa-jiddiyya li-taḥqīq al-waḥda al-waṭaniyya wa-al-ʿibra fī al-tanfīḏ [Dr. Mustafa Barghouti: The Beijing Declaration to end division is an important, advanced, and serious step to achieving national unity, but implementation is key],” July 23, 2024, link.

[10] Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, “ʿali fayṣal yudīn jarīmat ʾiġtiyāl al-qāʾid al-waṭanī al-kabīr ismaʿīl haniyya wa-yuʾakkid ʾanna al-jarīma lan taksir ʾirādat šaʿbina wa-muqāwamatahu [Ali Faisal condemns the assassination of the great national leader Ismail Haniyeh and asserts that the crime will not break the will of our people nor their resistance],” July 31, 2024, link.

[11] Adam Rasgon and Julian E. Barnes, “Hamas Official: ‘We’re Not Obstinate’ in Peace Talks on Gaza,” The New York Times, July 12, 2024, link.

[12] Yakoota Al Ahmad, “ḥamās: ‘ʾiʿlān bikīn’ ḫuṭwa ījābiyya ʿala ṭarīq al-waḥda al-filasṭīniyya [Hamas: ‘Beijing Declaration’ is a positive step on the path to Palestinian unity],” Anadolu Agency, July 23, 2024, link.

[13] NB: a version of the declaration which informed some of the first reports on the day of its announcement includes elements which are lacking in the subsequently published photographs of the texts, notably, explicit reference to UN General Assembly Resolutions 181 and 194, and UN Security Council Resolution 2334.

[14] Webangah, “radd fiʿl ḥarakat al-jihād al-ʾislāmī al-filasṭīnīyya ʿala ʾittifāq bikīn [The Palestinian Islamic Jihad movement’s response to the Beijing Agreement],” July 23, 2024, link.

[15] The PLO formally acknowledged Israel’s sovereignty in 1993, as part of the Oslo Accords; in return, Israel formally recognized the PLO as legitimate representative of the Palestinian people and the right of Palestinians to self-govern within portions of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Hamas and PIJ reject the Oslo Accords but have, under various circumstances, agreed to suspend hostilities with Israel. Hamas leaders have moreover suggested the group could be willing, if not to formally recognize Israel, then to accept de facto coexistence, under conditions including a full withdrawal of Israeli military and settlements from territories it occupied in 1967, i.e., the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem, and the establishment of a Palestinian state on those territories. See Yasser Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin, “Israel-PLO Recognition: Exchange of Letters between PM Rabin and Chairman Arafat,” September 9, 1993, link; Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements (Oslo I Accord), UN Doc. A/48/486, S/26560, September 13, 1993, link; and Tareq Baconi, Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance, Stanford University Press, 2018.

[16] Laura Zhou and Zhao Ziwen, “Palestinian factions agree to end division in pact brokered by China,” South China Morning Post, July 23, 2024, link.

[17] Jihad Harb, “shukran li-al-ḥukūma … jadīd ʾiʿlān bikīn [Thank you to the government … The novel element of the Beijing Declaration],” Watan, July 26, 2024, link.

[18] Omar Hilmi Al-Ghoul, “ʾījābiyyāt ḥiwār bikīn [The positives of the Beijing dialogue],” State of Palestine, July 24, 2024, link.

[19] Recognition of Israel is one of the bases upon which international actors such as the United States agree to engage with the PLO, thus providing “international legitimacy.”

[20] Hamada Faraneh, “natāʾij ḥiwār bikīn al-filasṭīnī [Results of the Palestinian Beijing Dialogue],” Al-Quds, July 29, 2024, link.

[21] Naila Khalil, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, July 25, 2024, link.

[22] Hani Al-Masri, “hal inhāra ittifāq bikīn ʾam jummida ʾila waqt al-ḥāja? [Has the Beijing agreement collapsed, or has it been frozen until needed?],” Al-Quds, July 30, 2024, link.

[23] Naila Khalil, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, July 25, 2024, link.

[24] Times of Israel, Israel, US, UAE Said to Have Held Secret Abu Dhabi Meeting on Gaza Postwar Plan, July 23, 2024, link.